In 2021, I designed and, in collaboration with PrusaLab, built the kinetic sculpture Fluidum — a permanent addition to the Czech pavilion at Dubai EXPO 2020. In today’s article, I would like to present its artistic concept, as well as share some technical insights. You will find out what technologies it’s based on, and how we actually managed to produce it in record time.

The artistic concept

A bit of artistic lingo first. The kinetic sculpture Fluidum represents a vertical water surface. It consists of 85 robotically controlled mirrors arranged in a strictly geometric pattern. Its main theme is embodied by the viewer and their reflection, which hypnotically ripples, morphs, and flows. The image of reality disintegrates into individual fragments, which the sculpture mixes, transforms, and puts into new, unexpected contexts.

When conceptualizing Fluidum, I was inspired by the experience of the prehistoric man gazing in wonder at the surface of the water in which he sees himself for the first time. It thus offers a parallel to the technology-laden present in which it is increasingly difficult to stop, think deeply and ask: “Who am I? Where am I going?”

The next step in evolution

The art piece is a continuation of the successful Reflexion installation from 2019. The preceding idea was awarded first place in the Signal Calling open call, which PrusaLab organizes every year together with the Prague Signal Festival (by the way, Czech-based artists can apply for this year’s edition of the festival until the end of March). Back then, I applied together with my friend and colleague Adam Cigler. The result, which we also built in PrusaLab, was an installation that was visited by almost 70,000 people at the festival that year. Reflexion is touring audiovisual art festivals around the world to this day.

Unlike Reflexion, however, Fluidum opens up a third dimension of movement of the mirrors towards the observer, making it possible to create a real mirror wave and pushing the boundaries of the viewer’s experience to a more intimate level.

Just like Reflexion though, Fluidum was developed in collaboration with Prusa Research in PrusaLab. This FabLab/prototyping workshop hybrid may as well be presented as a kind of a 21st-century art studio that allows for the creation of such complex works, exploring a new, appealing aesthetic augmented by digital technologies.

Fluidum’s kinematic concept

The basic building block of the installation is the so-called kinetic module with one mirror mounted on a platform moveable in three directions: the mirror can go sideways, up and down, and lift. In order to keep the whole art piece as thin as possible, we opted for the so-called Stewart platform as opposed to a linear actuator. This allows the individual mirrors to be controlled by the coordinated movement of three motorised joints.

Thanks to this special approach to the platform design, which is, by the way, also utilised by the James Webb Telescope, the art piece is nearly 15 centimetres thick by default, but also manages to extend the mirrors by another 22 centimetres forward.

Let’s get to work!

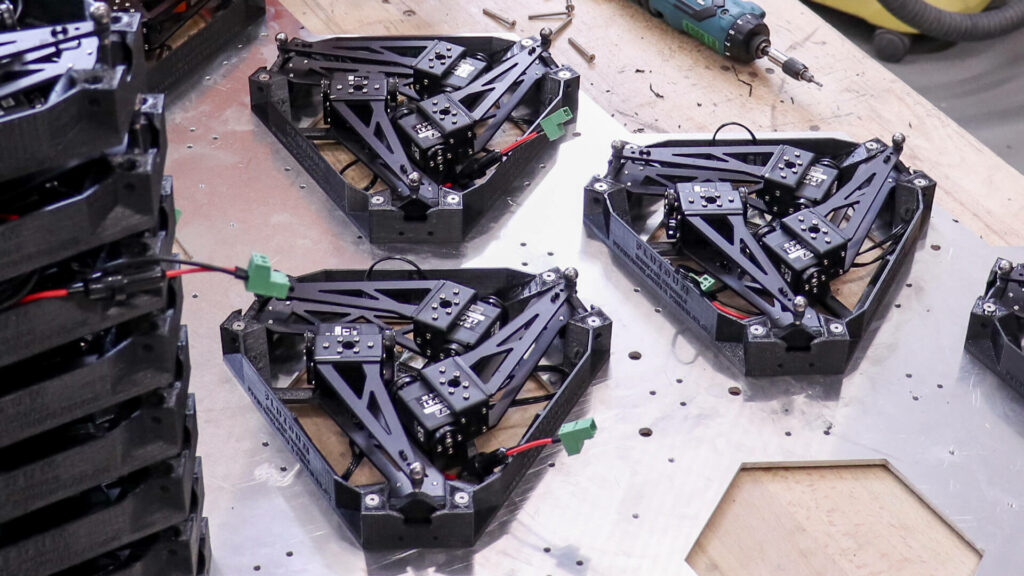

We had less than four months to build the whole thing, including prototyping the kinetic module, designing the electronics, circuit board, firmware, and finally testing and shipping it to Dubai. The beginning of the building process was a great example of rapid prototyping. Several prototypes were 3D printed at PrusaLab’s 3D printing farm, which allowed us to iterate the design daily. Not all parts were suitable for 3D printing, so it was necessary to secure suppliers of CNC cut aluminium, special ball studs, or find a subcontactor that would take care of the anodic coating, for example.

The design of each module consists of a 3D printed chassis and a 3D printed platform with a mirror attached. The chassis and the platform are connected to each other by three motorised articulated joints made from laser-cut aluminium, connected on one side by a hinge and on the other side by a ball-and-socket joint allowing the mirror to tilt in all directions.

The individual modules are then attached to a supporting structure made of CNC-cut aluminium sheets.

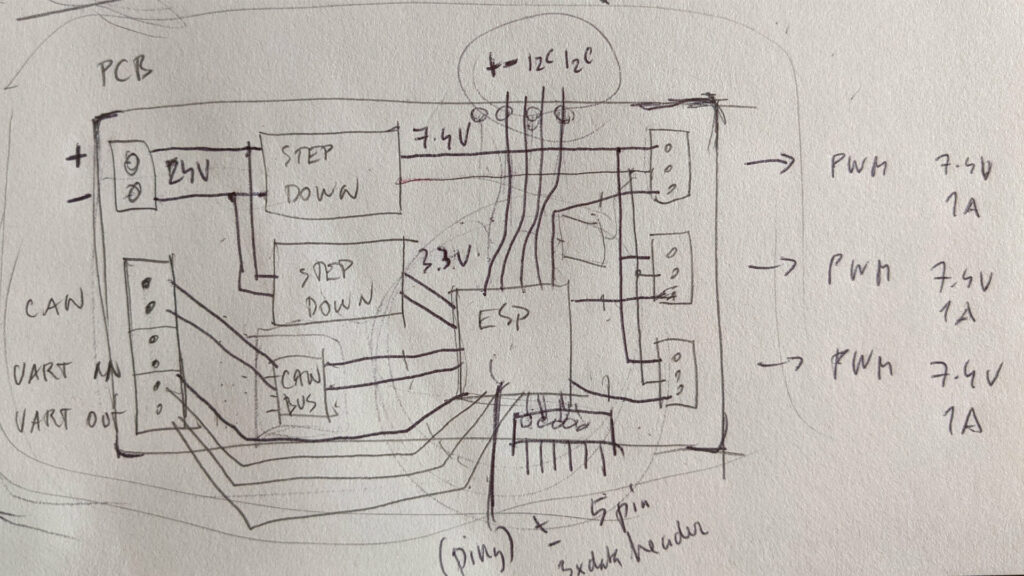

In order to make the mirror movement as smooth as possible, it is necessary to constantly synchronise the movement of all three motors in each of the 85 modules. Therefore, under each mirror there is a custom-designed printed circuit, at the heart of which is an ESP microcomputer that calculates a rather complex kinematic equation that converts the mirror position into motor position data. A major innovation lies in the servomotors used, which allow for serial communication via a half-duplex UART bus. With this setup, the control computer is able to receive information from the motors about their current position, load or temperature.

The individual modules are connected via CAN bus to the control computer, which constantly feeds them with new data about the mirror positions. The power supply consists of eighteen 12V power supplies. Thanks to our custom-designed firmware, it is possible, for example, to update the system in all 85 modules at once. Or to connect remotely using a web application with a simple user interface.

The printed circuit was designed by the experienced electrospecialist Matěj Suchánek in just two iterations. Although the lack of microchips and the overall lack of material on the market proved a bigger concern. Eventually, however, we were able to get everything or replace the missing parts with others, and so production was in full swing less than two months before the World Expo.

To assemble one module means to assemble 63 components, to screw 105 screws or to fit a printed circuit with 10 components. All of that 85 times. Still, we had twelve hours to assemble and run all the mirrors at once for the first time before packing them into a shipping pallet. The tension in the air during the final (and first) test was almost palpable.

Let’s go to Dubai!

Reflexion, designed for the demanding conditions of European light art festivals, is transported by the largest van. Fluidum, however, can be packed into one standard Euro pallet for air transport. Because that was the easiest way to haul it to Dubai from the Czech Republic.

In the Czech pavilion, where the sculpture is located, construction work was still underway two weeks before the opening. Among the hustle and bustle of workers from Pakistan and Sri Lanka, a two-person team of the author and the programmer began to attach the 300-kilogram mirror structure to the wall. Thanks to the cleverly designed magnetic pins, we could wait until just before the opening to mount the mirrors, thus avoiding the risk of them getting dirty or breaking during construction.

Although we flew to Dubai well prepared, we needed to finish the firmware on the spot. More importantly, we needed to add protective features to prevent power failure or remote overtaking. And, to not forget, we made a panic stop button 😅. Finally, I programmed the movement choreography of the mirrors.

Six months later

Fluidum operates seven days a week, twelve hours a day during the exhibition. Visitors are captivated from afar by the mysterious whirring of the servo motors, which not coincidentally resembles the tide. The unexpected transformations of the reflections in the mirror are interspersed with moments of dramatic stillness, when the mirrors do not move. Often the audience starts waving their hands, dancing and making all sorts of gestures in front of the mirrors. In fact, in today’s technological world there is a huge amount of interactivity, products and art that react to humans through various sensors. But in the case of Fluidum, which contains a pre-recorded choreography of mirrors, it is exactly the opposite — the visitor becomes the interactive element of the whole piece.

It is impossible to count how many viewers have already photographed or filmed their reflection in these moving mirrors. What is certain, however, is that this technicist sculpture will captivate everyone with its uniqueness.

If you have read this far, you might be interested in my other projects. You can find them at petrvacek.com or on my Instagram account.